1. Introduction: The Value of Biopsy Needles in Modern Medicine

In modern diagnostic medicine, biopsy needles play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between

clinical suspicion and definitive diagnosis.

A biopsy needle is a specialized medical instrument designed to obtain samples of cells or tissues from various organs with minimal invasion.

By providing direct access to cellular or histological material, biopsy needles enable pathologists and researchers to identify infections, inflammatory conditions, genetic abnormalities, and, most importantly, malignancies at an early stage.

The appeal of biopsy needles lies in their precision and versatility. From a simple fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA biopsy needle), which extracts individual cells, to a more complex needle core biopsy, which removes a small tissue cylinder, each method is tailored to the anatomical site and the diagnostic requirement.

This flexibility makes them indispensable tools not only for oncologists but also

for specialists in nephrology, pulmonology, endocrinology, hematology, and neurology.

For medical and research professionals, understanding the application directions, technical nuances, and procedural fundamentals of biopsy needles is essential.

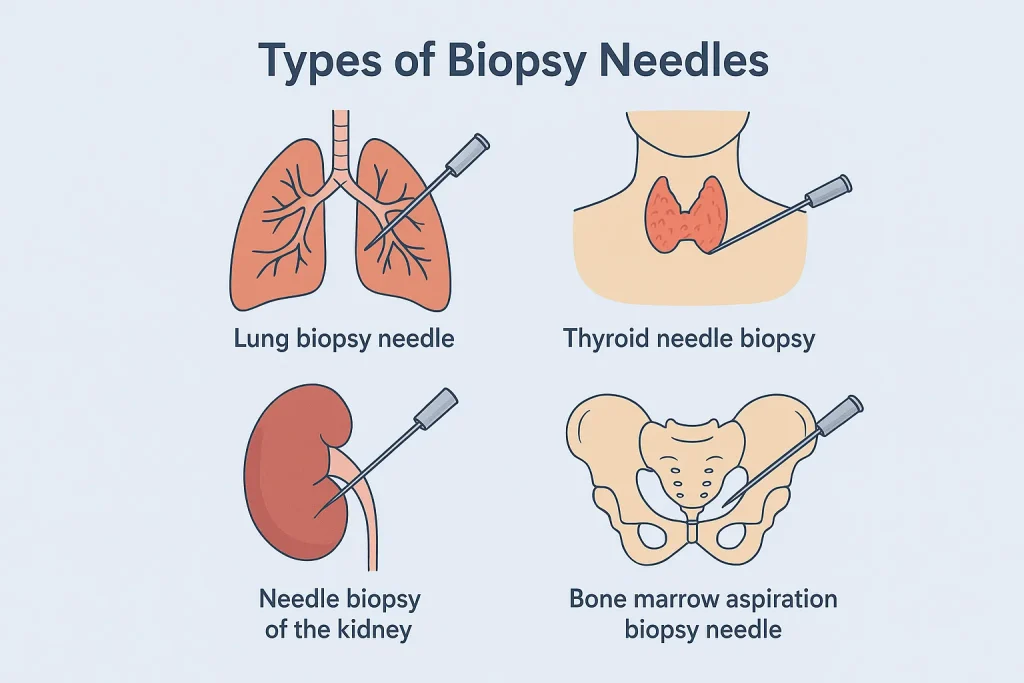

Whether the goal is to diagnose thyroid nodules with a thyroid needle biopsy, monitor rejection in a transplanted kidney through a kidney biopsy, or evaluate hematological disorders with a bone marrow aspiration biopsy needle, the correct choice and mastery of the technique directly impact diagnostic accuracy and patient safety.

Biopsy procedures are no longer confined to the field of oncology. They are increasingly applied in clinical research, industrial R&D, and personalized medicine, where high-quality tissue sampling supports genomic testing, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic innovation.

2. Fundamentals and Classification of Biopsy Needles

Biopsy needles are not a single category of instruments but rather a family of precision tools,

each optimized for specific diagnostic goals. The choice of needle depends on factors such as the target organ, the size of the lesion, and the type of analysis required (cytology vs histology).

2.1 What is a Needle Biopsy?

A needle biopsy is a minimally invasive procedure in which a physician uses a fine or core needle to extract a sample of cells or tissues for laboratory examination. Unlike surgical biopsies, needle-based techniques reduce patient trauma, shorten recovery time, and still provide sufficient diagnostic accuracy.

2.2 Common Types of Biopsy Needles

- – Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy Needle (FNA biopsy needle)

- – Core Needle Biopsy Needle (Needle core biopsy)

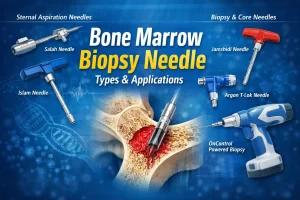

- – Bone Marrow Aspiration Biopsy Needle

- – Muscle Biopsy Needle

- – Lung Biopsy Needle

- – Thyroid Needle Biopsy

- – Needle Biopsy of the Kidney

2.3 Comparative Overview of Biopsy Techniques

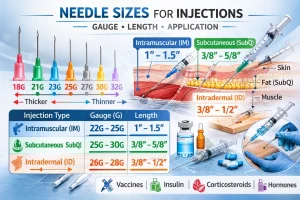

| Biopsy Type | Needle Gauge | Sample Type | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

| Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) | 22–27 G | Leukemia, lymphoma, and anemia | Thyroid nodules, breast lumps | Quick, low complication | Limited material |

| Core Needle Biopsy | 14–18 G | Tissue cylinder | Breast lesions, lung nodules | Detailed architecture | Higher risk of bleeding |

| Bone Marrow Aspiration | 11–15 G | Bone marrow cells | Leukemia, lymphoma, anemia | Critical for blood disorders | Painful, anesthesia required |

| Muscle Biopsy Needle | 14–16 G | Muscle tissue | Neuromuscular disease | Good pathology yield | Risk of infection |

| Lung Biopsy Needle | 18–20 G | Lung tissue | Lung cancer, ILD | CT-guided precision | Risk of pneumothorax |

| Kidney Biopsy Needle | 16–18 G | Renal tissue | Kidney disease, transplant | Detailed renal pathology | Hematuria risk |

3. Professional Techniques and Basic Procedures

The effectiveness of a biopsy needle is not only determined by its design but also by the skill and

precision of the operator. Mastering the procedural steps reduces patient risk, ensures high-quality samples, and increases diagnostic accuracy.

3.1 Pre-Procedure Preparation

- – Patient assessment: Review bleeding risks, allergies, and comorbidities.

- – Laboratory tests: Coagulation profile, platelet count.

- – Imaging guidance: Ultrasound, CT, or fluoroscopy.

- – Informed consent: Risks of bleeding, infection, and need for repeat biopsy.

3.2 Typical Procedural Steps

Details for FNA, Core Needle Biopsy, Bone Marrow Aspiration, and Kidney Biopsy procedures.

3.3 Post-Procedure Care

- – Monitor vital signs for several hours.

- – Watch for bleeding, pneumothorax, and hematuria.

- – Advise the patient to avoid strenuous activity for 24 hours.

- – In hospitalized patients, observe overnight if needed.

4. Organ-Specific Applications of Biopsy Needles

Biopsy needles are versatile tools, each adapted to specific organs and diagnostic requirements.

Mini case studies illustrate applications in thyroid, lung, kidney, bone marrow, and muscle biopsy contexts.

5. Fine Needle Aspiration vs Core Needle Biopsy

Both techniques are minimally invasive but differ in sample type, needle gauge, and diagnostic yield.

6. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Biopsy Needles

Q: What is a needle biopsy?

A: A minimally invasive procedure to collect cells or tissue.

Q: What is a fine needle aspiration biopsy?

A: Uses a thin needle for cytology; fast but limited sample.

Q: What is a core needle biopsy?

A: Uses a larger needle for tissue cores; detailed analysis is possible.

Q: Fine needle aspiration vs core biopsy?

A: FNA: screening; Core: histology and molecular.

Q: How long does a needle biopsy take?

A: FNA: 10–20 mins; Core: 20–40 mins; Kidney/Lung: 1–2 hours.

Q: What are the risks of a needle biopsy?

A: Bleeding, infection, pneumothorax, hematuria, depending on the organ.

Q: How soon are results available?

A: FNA: 24–48 hours; Core: 3–7 days.

Q: Do patients need anesthesia?

A: FNA: often none; Core/Bone marrow: local or sedation.

7. Future Trends and Research Directions in Biopsy Needles

The evolution of biopsy needles is closely tied to advances in precision medicine, imaging,

and biomedical engineering. Smart needles, AI-assisted image-guided biopsies, molecular and genetic applications, robotic systems, and industrial research uses are shaping the future.

8. Conclusion

Biopsy needles remain one of the most valuable tools in modern diagnostics and research.

From FNA to core, bone marrow to kidney, these instruments provide clinicians and scientists with direct access to biological material—a cornerstone for accurate diagnosis, personalized therapy, and biomedical discovery.

The future is moving toward smarter, safer, and more data-rich biopsy systems. With the integration of AI,

molecular diagnostics and robotic precision, biopsy needles will not only continue to define cancer diagnostics but also play a crucial role in translational research, regenerative medicine, and clinical trials.

For healthcare and research professionals, mastering both the technical fundamentals and the strategic applications of biopsy needles is essential for advancing patient care and scientific innovation.