I. Introduction : L'équation de sécurité

Dans l'environnement à forts enjeux des soins de santé modernes, la marge d'erreur est microscopique. Les infections nosocomiales (HAIs) restent un adversaire redoutable, coûtant au seul système de santé américain des milliards de dollars par an et affectant des centaines de milliers de patients en Europe.

Alors que les protocoles systémiques se concentrent souvent sur une hygiène environnementale générale, la procédure invasive la plus courante en médecine - l'injection - reste une ligne de front critique dans la prévention des infections.

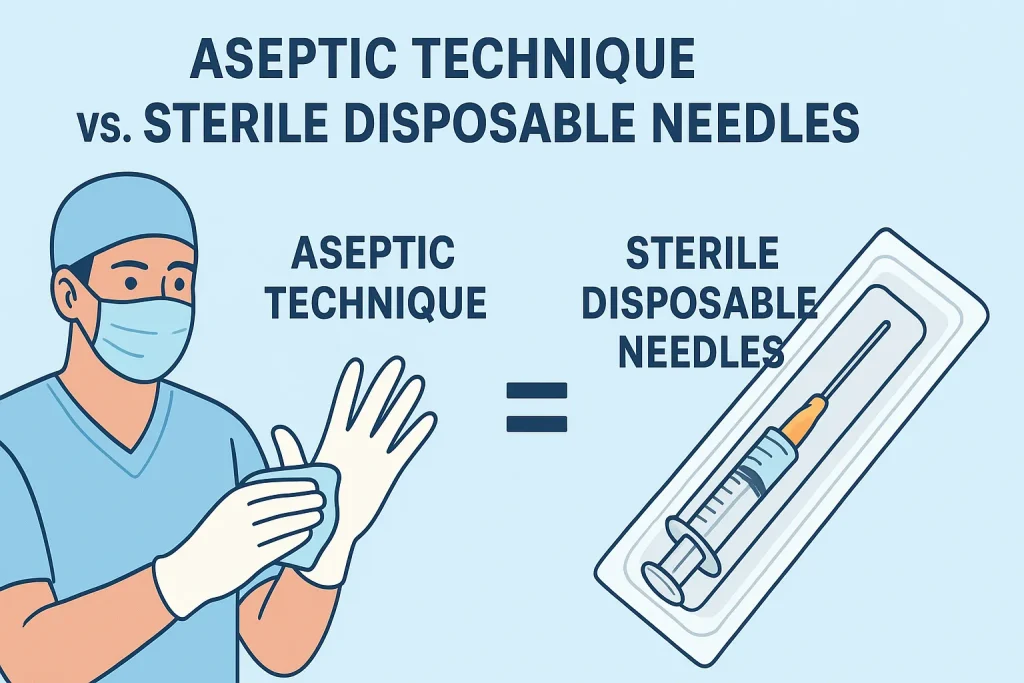

Pour l'œil non averti, la sécurité semble garantie par l'emballage. Cependant, la prévention des infections n'est pas un produit unique, c'est une équation. Sécurité = (intégrité stérile du dispositif) × (technique aseptique de l'utilisateur)

Si l'une des variables de cette équation est égale à zéro, le résultat est un échec.

Cet article explore la relation symbiotique entre le “matériel” - l'ordinateur - et le "système" - l'ordinateur. aiguille stérile jetable-et le “logiciel” - le technique aseptique. Nous démonterons l'idée fausse selon laquelle il s'agit de préoccupations distinctes et démontrerons pourquoi une fabrication de haute qualité et un comportement clinique rigoureux doivent s'aligner pour protéger la vie des patients.

II. Le “matériel” : Qu'est-ce qui rend une aiguille “stérile” ?

Une aiguille n'est pas simplement un tube pointu ; c'est un dispositif médical soumis à des normes d'ingénierie rigoureuses. Lorsqu'un clinicien prend un emballage, il s'appuie sur un processus industriel complexe conçu pour éliminer tous les micro-organismes viables.

Normes de fabrication : Au-delà de l'acier

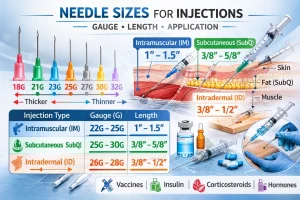

La production de aiguilles stériles jetables est régi par des normes internationales strictes, notamment ISO 7864 (Aiguilles hypodermiques stériles à usage unique).

La stérilité ne se limite pas à la propreté ; elle exige un processus validé pour atteindre un niveau d'assurance de stérilité (SAL) de 10-⁶, ce qui signifie qu'il y a moins d'une chance sur un million qu'un micro-organisme viable reste sur le dispositif.

Tableau 1 : Méthodes de stérilisation courantes pour les Aiguilles médicales

| Fonctionnalité | Oxyde d'éthylène (EtO) | Irradiation gamma |

|---|---|---|

| Mécanisme | Pénétration de gaz chimiques qui perturbent l'ADN/l'ARN. | Photons de haute énergie qui rompent les liaisons chimiques dans les agents pathogènes. |

| Adéquation de l'emballage | Nécessite un emballage perméable à l'air (par exemple, du papier de qualité médicale) pour permettre l'entrée et la sortie des gaz. | Compatible avec les scellés hermétiques en aluminium ou en plastique. |

| Avantages | Doux pour les matériaux ; idéal pour les plastiques complexes. | Pas de résidus chimiques ; stérilité immédiate ; forte pénétration. |

| Considération | Nécessite un temps de dégazage pour éliminer les résidus. | Peut provoquer une décoloration ou une fragilité de certains polymères s'il n'est pas pris en charge. |

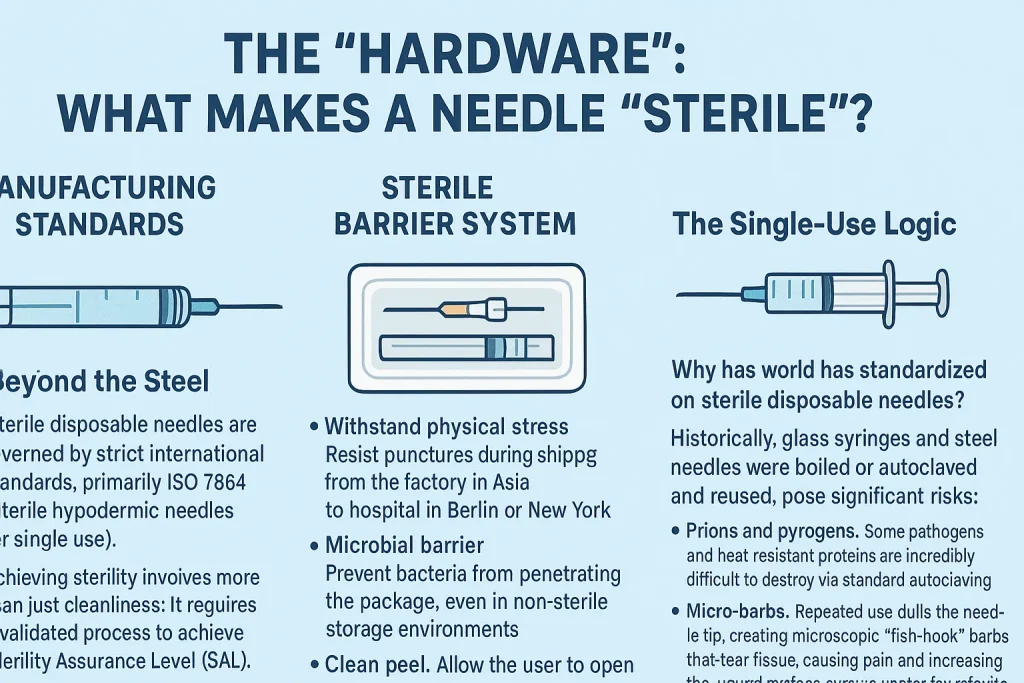

Le système de barrière stérile

Le héros méconnu de la sécurité des aiguilles est l'emballage. Une aiguille n'est stérile que si elle est scellée. Les fabricants de qualité investissent massivement dans l'emballage des aiguilles. Système de barrière stérile (SBS). Cet emballage doit :

- Résiste au stress physique : Résister aux perforations pendant le transport de l'usine en Asie à l'hôpital à Berlin ou à New York.

- Barrière microbienne : Empêchent les bactéries de pénétrer dans l'emballage, même dans les environnements de stockage non stériles.

- Peeling propre : Permettre à l'utilisateur d'ouvrir l'emballage sans le déchirer, ce qui crée de la poussière de papier (contamination particulaire) ou fait rebondir l'aiguille sur une surface non stérile.

La logique de l'usage unique

Pourquoi le monde s'est-il standardisé sur aiguilles stériles jetables? Historiquement, les seringues en verre et les aiguilles en acier étaient bouillies ou stérilisées à l'autoclave et réutilisées. Cela présentait des risques importants :

- Prions et pyrogènes : Certains agents pathogènes et certaines protéines résistantes à la chaleur sont extrêmement difficiles à détruire par l'autoclavage standard.

- Micro-barbes : L'utilisation répétée émousse la pointe de l'aiguille, créant des arêtes microscopiques en forme d'hameçon qui déchirent les tissus, provoquant des douleurs et augmentant la surface de la plaie - un vecteur d'infection.

- Fatigue des matériaux : Le chauffage répété affaiblit l'acier, ce qui augmente le risque de rupture.

Aujourd'hui, “jetable” est synonyme de “sécurité”. Il garantit que chaque patient reçoit un dispositif vierge, tranchant et certifié stérile.

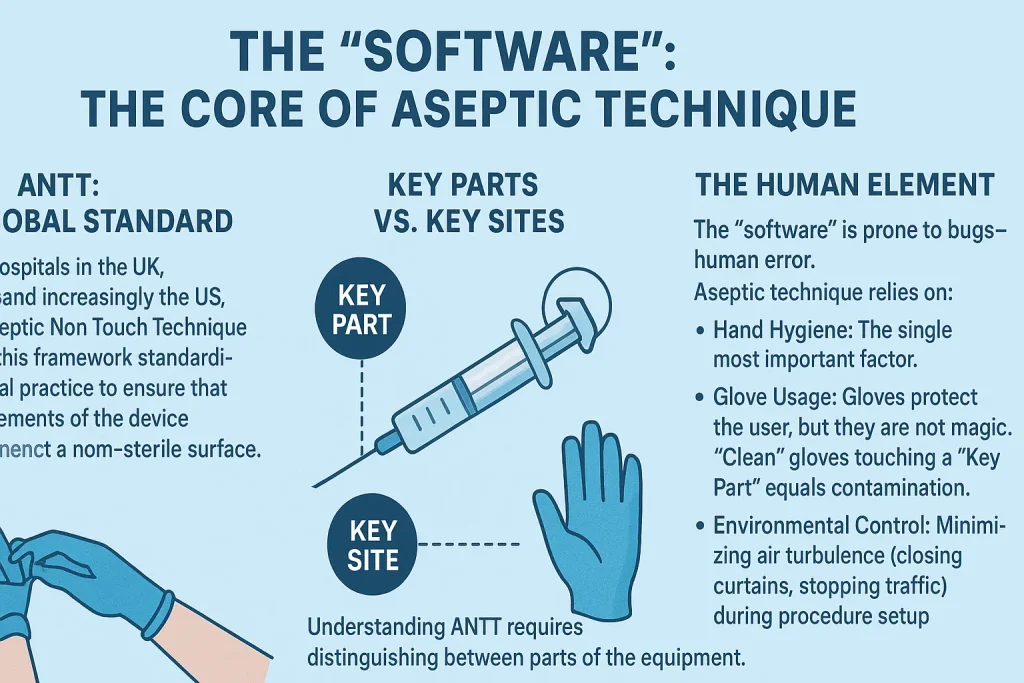

III. Le “logiciel” : Le cœur de la technique aseptique

Si l'aiguille stérile est l'outil, Technique aseptique est le système d'exploitation. Même l'aiguille la plus parfaite devient un risque biologique dès qu'elle touche une surface non stérile.

ANTT : La norme mondiale

Les hôpitaux modernes du Royaume-Uni, de l'Australie et, de plus en plus, des États-Unis, utilisent Technique aseptique sans contact (ANTT). Ce cadre standardise la pratique clinique afin de garantir que les éléments clés du dispositif n'entrent jamais en contact avec une surface non stérile.

Pièces maîtresses et sites clés

Pour comprendre l'ANTT, il faut faire la distinction entre les parties de l'équipement et les zones du patient.

Tableau 2 : Définition des zones de non-droit

| Catégorie | Définition | Exemples (ne doivent JAMAIS être touchés) |

|---|---|---|

| Pièces maîtresses | Parties de l'équipement qui doivent rester stériles. Si elles sont contaminées, le patient est directement exposé. | - La tige et le biseau de l'aiguille - L'embout de la seringue (Luer slip ou lock) - L'intérieur du capuchon de l'aiguille - La tige du piston (dans certains protocoles stricts). |

| Sites clés | Zone du patient dans laquelle le dispositif médical pénètre. | - Le site d'injection de la peau nettoyée - La plaie ouverte - Le site d'insertion du cathéter |

L'élément humain

Le “logiciel” est sujet à des bogues, c'est-à-dire à des erreurs humaines. La technique aseptique repose sur :

- Hygiène des mains : Le facteur le plus important.

- Utilisation du gant : Les gants protègent les utilisateur, mais ils ne sont pas magiques. Des gants “propres” qui touchent une “pièce clé” sont synonymes de contamination.

- Contrôle de l'environnement : Minimiser les turbulences de l'air (fermer les rideaux, arrêter le trafic) pendant la mise en place de la procédure.

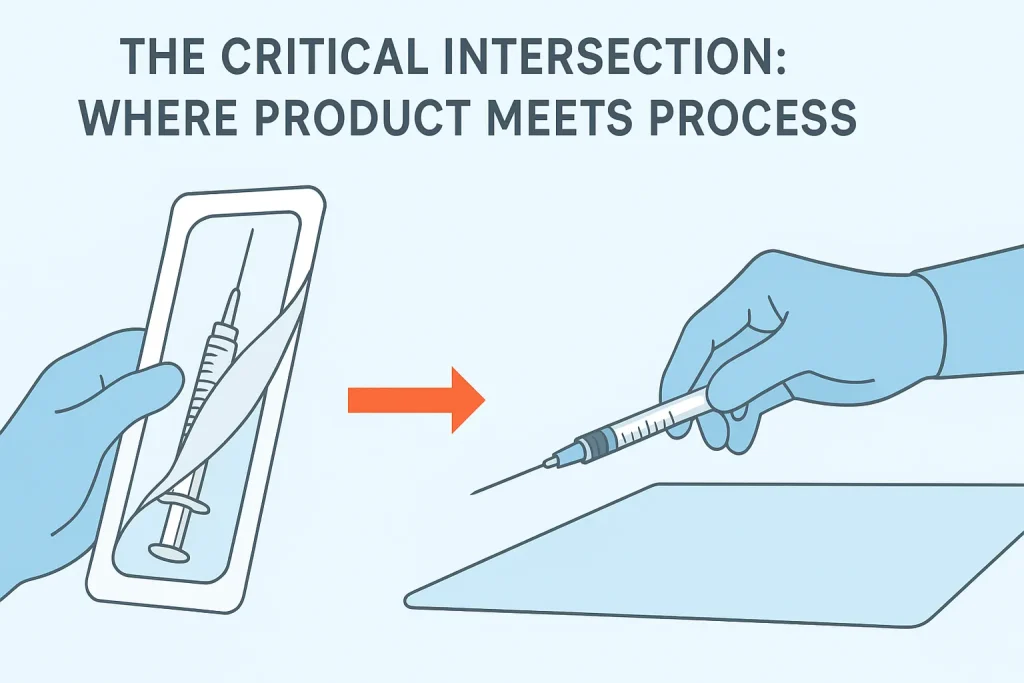

IV. L'intersection critique : Le point de rencontre entre le produit et le processus

Le moment où le risque est le plus élevé est celui où le produit quitte son emballage. C'est là que la conception de la fabrication et les compétences cliniques se croisent.

Le moment de l'épluchage

Un emballage mal conçu fait obstacle à l'utilisateur. Si le papier se déchire ou si le sceau est trop serré, le clinicien peut se débattre, ce qui entraîne :

- Le recul : L'aiguille sort par à-coups et heurte un plateau non stérile.

- Contact : Le doigt de l'utilisateur effleure le moyeu lorsqu'il essaie d'ouvrir l'emballage.

Rôle du fabricant : Les principaux fabricants conçoivent des systèmes “peel-pack” avec des couches de séparation distinctes et des languettes de préhension, permettant une ouverture douce et contrôlée qui favorise un “transfert sans contact” directement sur un champ stérile ou sur la seringue.

Mécanismes de sécurité et stérilité

Aiguilles à insuline rétractables et les seringues de sécurité sont souvent commercialisées pour prévenir les blessures par piqûre d'aiguille (sécurité du personnel soignant), mais elles favorisent également la technique aseptique.

- Le risque de rebouchage : Dans les scénarios d'injection traditionnels, le rebouchage d'une aiguille est la principale cause de contamination accidentelle (et de blessure).

- La solution de sécurité : En enclenchant un mécanisme de sécurité qui recouvre l'aiguille immédiatement après son retrait, le clinicien n'a plus besoin de manipuler une aiguille contaminée, ce qui préserve l'intégrité aseptique de l'environnement immédiat.

Étude de cas : L'escalade de l'asepsie

- Injection standard (propre/standard aseptique) : Vaccination contre la grippe. Le site est nettoyé. L'aiguille stérile est fixée. L'injection est effectuée. Le risque est géré par la protection standard “Key Part”.

- Hémodialyse (chirurgie aseptique) : Insérer un Aiguille à fistule. Comme cette aiguille accède directement à la circulation sanguine à haut débit, le risque de septicémie est plus élevé. “Une technique chirurgicale aseptique est nécessaire : gants stériles, champ stérile plus large et souvent un masque. Dans ce cas, la qualité du capuchon protecteur de l'aiguille et l'ergonomie de l'embout sont essentiels pour garder le contrôle tout en portant des gants stériles encombrants.

V. Idées fausses et pièges courants

Même les professionnels expérimentés peuvent être victimes de mythes subtils qui compromettent la sécurité.

Mythe 1 : “L'aiguille est stérile, je peux donc la poser sur un plateau”.”

- La réalité : Si ce plateau n'est pas recouvert d'un drap stérile et ne constitue pas un champ stérile, il est simplement “propre”. Une aiguille stérile placée sur un plateau propre est désormais contaminée. Elle doit rester dans son emballage ou être bouchée jusqu'au moment de son utilisation.

Mythe 2 : “Je porte des gants, je peux donc toucher l'aiguille”.”

- La réalité : Les gants d'examen standard sont propres, mais non stériles. Ils proviennent d'une boîte exposée à l'air. Le fait de toucher le moyeu (une pièce clé) avec un gant propre transfère les bactéries de la boîte/de l'air vers le trajet du fluide.

Mythe 3 : “Le paquet a l'air en bon état, il est donc sûr”.”

- La “fausse sécurité” : Des microperforations peuvent se produire si les boîtes sont écrasées ou stockées de manière inappropriée.

- Meilleure pratique : Les utilisateurs doivent vérifier l'intégrité du sceau avant de le décoller. Pour ce faire, les fabricants utilisent des indicateurs de stérilisation à couleur changeante sur l'emballage afin de prouver que le produit a subi le processus de stérilisation.

Tableau 3 : Comparaison des techniques

| Niveau technique | Objectif | Procédure type |

|---|---|---|

| Technique propre | Réduire le nombre de micro-organismes. | Prise de la tension artérielle ; examen physique de routine. |

| Technique aseptique (ANTT) | Empêcher l'introduction de micro-organismes dans les sites clés. | Insertion IV ; injections IM ; pansement. |

| Technique chirurgicale stérile | Éliminer TOUS les micro-organismes d'une zone. | Chirurgie majeure ; insertion d'un cathéter central. |

VI. Conclusion : L'engagement du fabricant

Dans la lutte contre l'infection, la frontière entre le succès et l'échec est tracée à la pointe d'une aiguille. Nous devons reconnaître que technique aseptique est le comportement, et le aiguille stérile jetable est le catalyseur.

Pour le clinicien, cela signifie l'adhésion aux principes de l'ANTT et la vigilance à l'égard des “pièces maîtresses”. Pour le fabricant, cela signifie un engagement inébranlable envers les normes ISO, un emballage robuste à barrière stérile et des conceptions ergonomiques qui minimisent les difficultés de manipulation.

Les prestataires de soins de santé et les responsables des achats doivent regarder au-delà du prix unitaire. Le choix d'aiguilles stériles jetables de haute qualité implique d'évaluer l'intégrité de l'emballage, la clarté de l'étiquetage et la fiabilité des mécanismes de sécurité.

En investissant dans du “matériel” de qualité supérieure, les hôpitaux réduisent la charge cognitive du personnel et facilitent l'exécution du “logiciel” de la technique aseptique, ce qui permet en fin de compte de protéger la personne la plus importante dans la pièce : le patient.

VII. Sources autorisées et lectures complémentaires

- Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS (ORGANISATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTÉ)): Directives de l'OMS sur la prise de sang : Meilleures pratiques en matière de phlébotomie. (Genève : Organisation mondiale de la santé ; 2010).

- Centres de contrôle et de prévention des maladies (CDC): Guide de prévention des infections en milieu ambulatoire : Attentes minimales pour des soins sûrs.

- L'Association pour une pratique aseptique sûre (ASAP) : Cadre de pratique clinique ANTT®. (www.antt.org)

- Organisation internationale de normalisation (ISO):

- ISO 7864:2016 - Aiguilles hypodermiques stériles à usage unique.

- ISO 11607 - Emballage des dispositifs médicaux stérilisés en phase terminale.

- Institut national pour la santé et l'excellence des soins (NICE): Infections associées aux soins de santé : prévention et contrôle dans les soins primaires et communautaires.